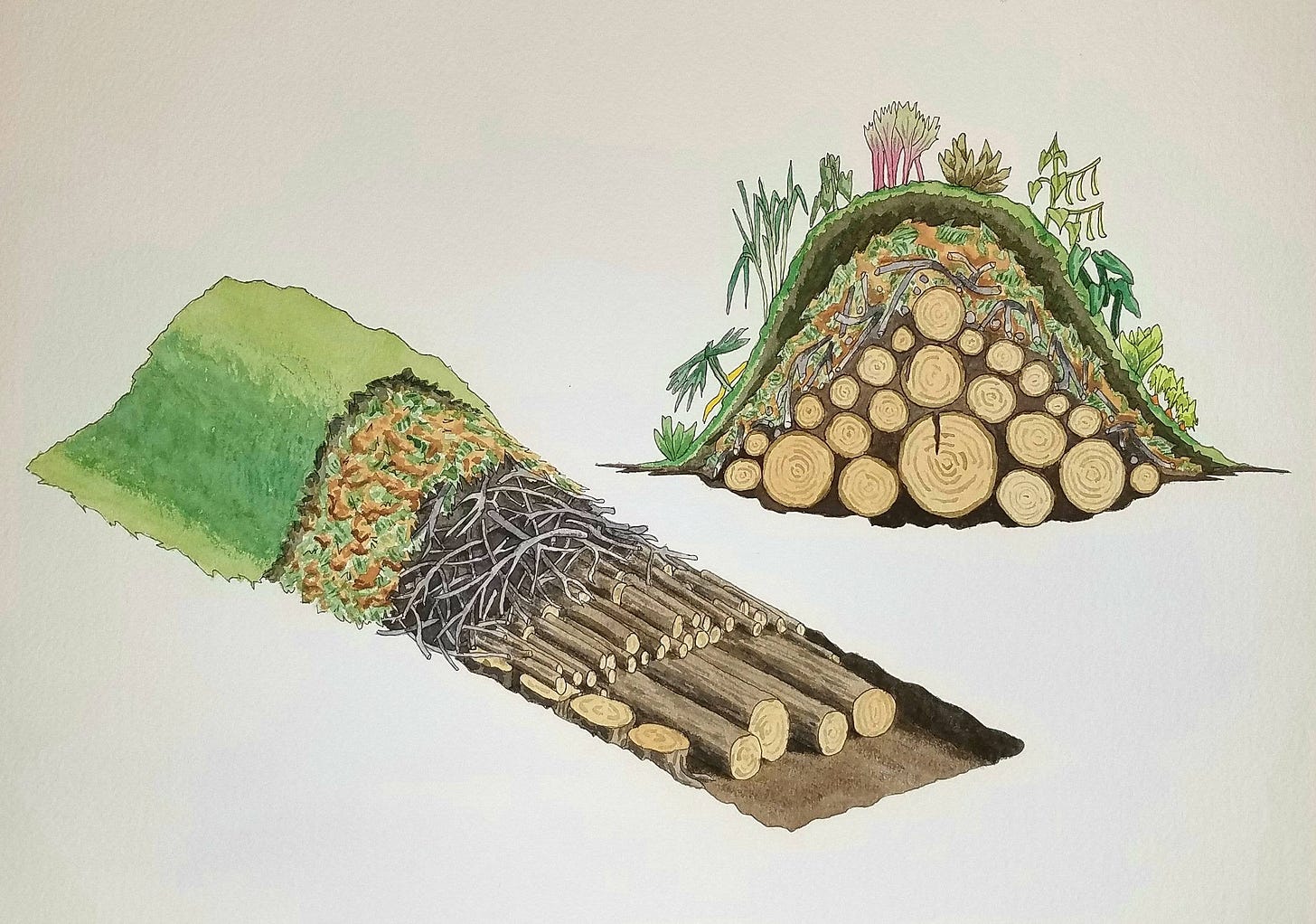

Hügelkultur (“hill culture”) is a method of raised bed planting in which deadfall and other excess woody material is buried beneath layers of biomass, compost, and soil in a mound shape, such that the woody biomass in the center gradual decomposes, retaining water and slowly releasing nutrients over time. The system is anecdotally reported to require less maintenance and less compost than traditional flatland planting, and it serves to remove unwanted woody biomass, potentially sequestering that carbon in the soil.

Although often claimed to be a “centuries old technique,” the specific term and process can be traced back to Herrman Andrä1 in 1962, and later popularized further by Austrian permaculturalist Sepp Holzer,2 although undoubtedly burying wood and planting crops in the soil above it has long been practiced by various peoples throughout human history.

Benefits

Despite widespread hügelkultur advocacy in permaculturalist circles,3 there have been very few scientific publications on specific claims of efficacy, and no peer-reviewed studies. Intuitively from a permacultural perspective, some benefits do appear obvious:

energy loops are kept closed by retaining biomass on the property, sequestering the carbon on-site instead of burning and releasing into the atmosphere

slower decomposition of the wood (by merit of being buried and removed from the influences of weathering and oxygen) means slower nutrient release

mound structure means less stooping and more surface area for growing

no-till practice maintains structure of the soil and prevents nutrient depletion

can be shaped to direct rainwater into catchment basins

Some apparent benefits sound like they should work in principle, and anecdotally have some evidence to support them, but have yet to be rigorously and quantitatively studied:

spongifying wood holds water, which should mean less watering requirements

slowly decaying biomass under the mound should mean less compost needs to be applied to the topsoil each growing season

But there are also some not-so-obvious downsides to the practice, as well as traps to fall into for the inexperienced.

Mound Collapse

The nature of a hügelkultur bed lends itself to collapse over time as the bulky wood heart of the mound decays and turns into humus. While this is a good thing from soil-building perspectives, it causes the physical collapse of the mound as well as compaction of the soil within.4 Both of these facts are detrimental to perennials planted in the bed. Therefore, it's generally recommended that hügelkultur beds be used primarily for planting annuals or wildflower gardens.

Over-fertilization

A lot of compost and biomass goes into making a hügelkultur bed, at least according to most sources, and so it is very easy to over-fertilize.5 As plants can only uptake so many nutrients in a growing season, the excess will run off with the rains and potentially pollute waterways downstream.

Year One Nitrogen Deficiency

Counter-intuitively, in spite of how easy it is to over-fertilize a hügelkultur bed, most gardeners find a common problem is a lack of nitrogen in the first year as the wood begins to breakdown, a phenomenon known as “nitrogen drawdown.”6 Packing nitrogen-rich green mulch immediately adjacent to the wood during construction of the mound can help alleviate this problem. Using only semi-rotted wood can help, too.

Anaerobic Decomposition

The woody biomass buried beneath layers of compost and soil can potentially turn anaerobic and acidic under certain soil conditions, such as in perched water, where groundwater is held by an impermeable layer like clay. Digging a trench into such a soil for a hügelkultur bed could potentially very easily create this sort of anaerobic, anti-microbial environment.7

Swales and the Buoyancy of Wood

Non-decomposed wood is naturally buoyant, and this presents a problem when hügelkultur mounds are used as swales to direct and contain large volumes of water. If the mound becomes saturated, the wood can force its way up and out of the soil, destroying the structure of the mound and ultimately causing a flood incident, as has happened on at least one occasion.8 Contributing to the problem is the recommendation not to plant perennials in hügelkultur mounds, the roots of which serve to anchor true swales during storm events. It is therefore recommended that hügelkultur mounds be built primarily on flatland and not be used as catchment basins for large volumes of water.

Weeds

The large surface area of disturbed soil after the initial creation of a hügelkultur mound presents lots of fantastic habitat for opportunistic weeds, which will quickly colonize the bed.9 Heavy mulching or cardboard layering is recommended to keep weeds in-check.

Types of Wood to Use

Do not use wood species that are allelopathic or inhibit the growth of other plants (eg. black walnut), resist decay (cedar), green trees that sprout easily (willows), or treated/painted woods (railroad ties).10 Also avoid trees like firs and pines that can leach tannins into the soil and turn it acidic. The best woods to use are those like apple, alder, maple, oak, poplar, and acacia.11 Other local materials can also be substituted for wood if available, such as rice grass.12

Often accompanying hügelkultur advocacy are claims that it mimics how soil is built naturally in forest biomes through litterfall. While there are certainly situations in which tree trunks and branches may become buried as in a hügelkultur mound (eg. landslides and floods), soil-building through litterfall generally occurs on the soil surface. Similarly, the decaying logs in a hügelkultur mound cannot act as “nurse logs” when they are buried and inaccessible to surface-dwelling biota like insects, reptiles, rodents, fungi, lichens and mosses. In many if not most cases, your local ecology may be better served by keeping litterfall on the soil surface.13

Ultimately, the primary purpose of hügelkultur is to utilize excess available, local materials and build soil with them instead of allowing them to go to waste or take up valuable growing space. As a method of raised bed construction, they have their advantages and disadvantages, and may make sense in some contexts more than in others. As usual when designing a permacultural landscape, closely examine the land and environment, note the changes over the seasons, and create a system that mimics natural processes as closely as possible while maintaining closed energy loops and nutrient cycles. ~

Chalker-Scott, L. (2017). Hugelkultur: what is it, and should it be used in home gardens? Washington State University Extension Services.

Holzer, S. (2011). Sepp Holzer's Permaculture: A Practical Guide to Small Scale, Integrative Farming and Gardening. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Jenkin, E. (2022). How to Build Hugelkultur Beds and Why You Need Them. New Life on a Homestead.

Chalker-Scott. (2017).

Ibid.

Jenkin. (2022).

Gardening in Canada. "HÜGELKULTUR EXPLAINED BY SOIL SCIENCE. THE BENEFITS, THE ISSUES & THE HISTORY. | Gardening in Canada." Youtube, 8 Feb. 2021.

Spirko, J. (2015). Don’t Try Building Hugel Swales – This is a Very and I Mean Very Bad Idea. Permaculture News.

Chalker-Scott. (2017).

Luo, Q. L., Hentges, C., & Wright, C. (2020). Sustainable landscapes: Creating a hugelkultur for gardening with stormwater management benefits. Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service.

Jenkin. (2022).

Laffoon, M. (2016). A Quantitative Analysis Of Hugelkultur And Its Potential Application On Karst Rocky Desertified Areas In China. Western Kentucky University Honors College Capstone Experience.

Chalker-Scott. (2017).

Loved this. Would like a follow-up on planting Norman hedgerows around a garden to prevent soil depletion.