Hedgerows, also known as shelterbelts, are rows of woody vegetation that line the borders of fields and are managed to keep their linear shape.1 Hedgerows often form networks, intersecting and creating a landscape known by the French word bocage. Though the quintessential hedgerow type is to be found in the Normandy region of France, hedgerows and their landscapes exist across the world. Unfortunately, outside of Europe studies on them are scarce.

Some hedgerows have been dated to Roman times, but many likely arose later in the Middle Ages when fields were cleared from woodland, leaving remnant trees and brush along the edges.2 Hedgerows were further expanded during the period of enclosure that began at the start of the 18th century, and have since become an important part of the rural landscape.

Hedgerows provide a multitude of ecological and social benefits to their landscapes and the people in them. Far from being simply vestigial remnants of the rural past, they have an important future part to play in rewilding suburbia and in transforming the agricultural landscape away from being dominated by corporate monoculture operations and towards systems that work in tandem with the native ecology.

Hedgerows as Tools in a Permaculturist’s Toolkit

Agricultural technologies are tools that humans can use to bend and shape the natural landscape to our whim. While traditionally these technologies have been used to push back against nature and carve “productivity” out of ecology, just as fields for plowing and grazing have long been carved out of verdant woodland, it need not be this way. Agricultural technologies can and should be utilized to promote both human and ecological flourishing, as in the end the proliferation of ecological value benefits humans as much (perhaps more than!) our efforts to turn nature into a factory that satisfies manufactured desires.

Hedgerows are a premier example of an agricultural technology managed by humans that is known mostly by its association with farming and land enclosure, with ecological benefits that are often overlooked. The what and why of these hedgerow functions is important to understanding the how of hedgerow creation and management. The following is a summary of those ecological benefits.

Shelter from the Wind

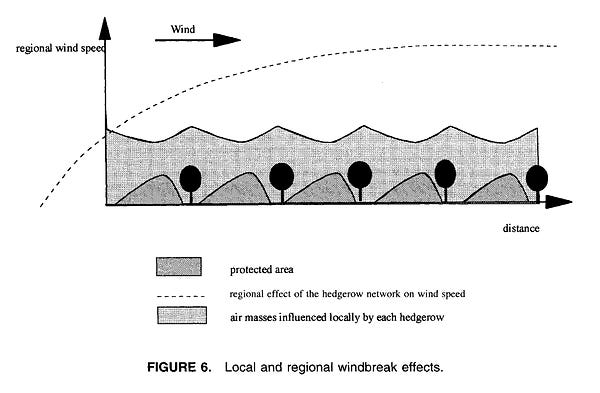

The most obvious benefit of hedgerows and shelterbelts is in the name: shelter. A large mass of trees and brush, oriented perpendicular to the prevailing wind, greatly reduces incoming wind speed downwind for up to 8-10 times the height of the hedgerow.3 This effect peaks at 4-5 times the hedgerow height.4 A hedgerow need not be extremely tall to offer wind protection, though. Even a height of just 2 meters is enough for substantial wind reduction.5 A summary of the cumulative effects of wind speed on local microclimates is shown below.

Although isolated hedgerows work to protect immediately adjacent land plots from the wind, a greater effect is noticed when hedgerows are widespread and closely spaced enough to form a bocage network. In this case, the bocage creates a surface roughness on the landscape that serves to separate winds aloft from surface air masses, reducing the flux between them.6 Bocage landscapes are therefore much less windy due to this cumulative effect than they otherwise would be.

In comparison to solid windbreaks like walls, hedges perform better at providing shelter, as their semi-permeable nature reduces the amount of turbulence, lengthening the downwind area protected.7

Shelter from Airborne Particles

In addition to protection from the wind, hedgerows act as a barrier to substances blown by the wind. Micropropagules such as spores, dust, and seeds, as well as herbicides, pesticides, fungicides, and airborne pests can all have their areas of dispersion contained by hedgerows.8910 Hedges planted in the medians of urban canyons have also been shown to reduce local pollution levels.11

Shelter from Predators

Hedges as a replacement for fences can also function in the role of boundary protection, whether as an impassable barrier for animal stock, predators, or other humans. They must remain managed by humans to do so, though. An overgrown hedge eventually becomes permeable, at least to wildlife. Top or coppice shrubs to stimulate thick growth.

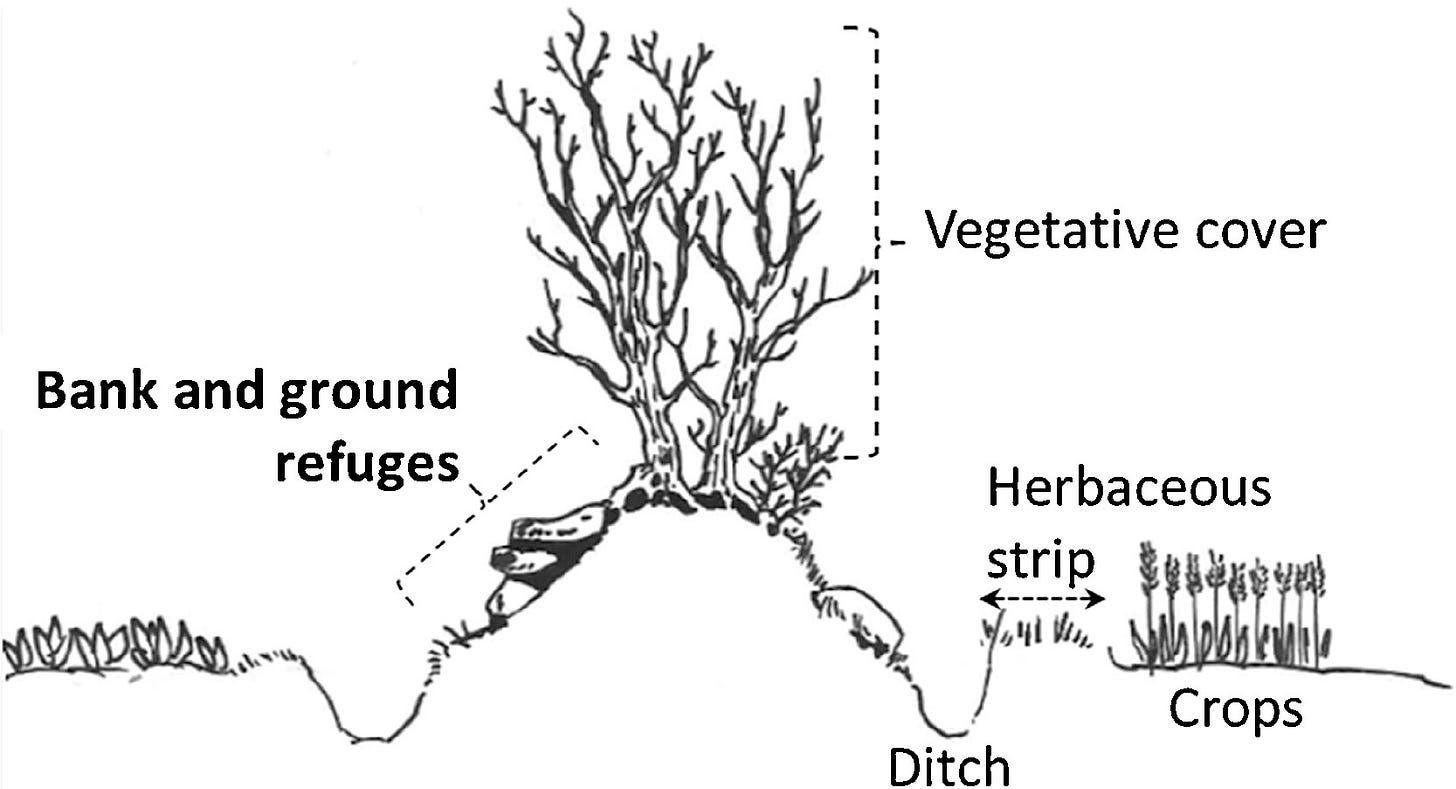

In Africa, villages are often surrounded by hedges as a sort of natural wall.12 Psychologically, the feeling of enclosure contributes to a sense of safety among people.1314 Hedgerows with larger banks and more ground refuges host not only a greater abundance and diversity of animals, but also larger species and those higher in the trophic (food) web.15

Erosion Control

Accompanying the living portion of the hedge is an adjacent drainage ditch that serves to carry irrigation water in the summer months and rainfall runoff in the winter.16 In general, there are three main functional subunits of hedgerows in a bocage landscape, depending on their function with regards to water control:17

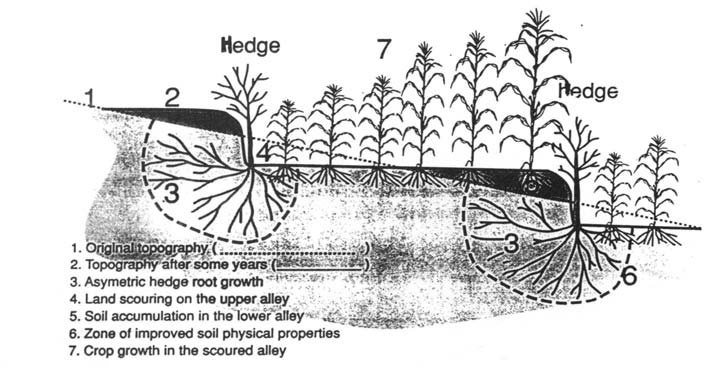

those perpendicular to the slope that trap water which accumulates in the superficial soil layers during rain events. These tend to form terraces on the landscape as silt is trapped behind them

those parallel to the slope that carry rainwater from the terraces to the main waterways

those that line floodplains, which serve to limit the ingress of floodwaters

Water Filtering

Besides directing the flow of water, the plants in hedgerow communities can also filter rainwater runoff and irrigation. They have been shown to aid the denitrification of waterways,1819 although on the hillslope and catchment basin scale the effect is reduced due to contamination of groundwater aquifers by past fertilizer application.20 The plants also serve as biofilters for other chemicals and pathogens.21 Similarly, vegetation in hedgerow waterways has been shown to remove floating biomass, lowering organic production by microorganisms and aiding water quality.22 The large roots of trees and bushes in a hedgerow can often penetrate deep below superficial soil horizons, thereby aiding water percolation into aquifers.23

Woodland Refuge

Hedgerows are an important habitat for native species, serving as a source of nectaries for pollinators and as a shelter and food source for small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and insects, which improves the biodiversity of adjacent farms.24252627 They serve as corridors for the dispersal of woodland plant and animal species, particularly if connected with woodland themselves.28

A greater abundance of predator insects and parasitoids in hedgerows also provides ecological benefits for adjacent crops, as these can range up to 100m away from the hedgerow in search of prey.29

Edge Effects

Hedgerow environments tend to be brighter than true woodland habitats due to their managed, linear shape and are more similar to woodland margins.30 This makes them excellent candidates for "food forest" systems along the margins of a residential property.31

The heterogeneous nature of a bocage landscape dominated by a chequerboard of fields bordered by hedgerows creates a multiplication of edge effects, in which fluxes across plots are both disrupted and facilitated. This results in an increase in local biodiversity, a reduction in pest and disease pressure, and overall a more anti-fragile ecology that is resilient to climatic or ecological shocks.32 Intentionally facilitating these edge effects on larger scales by combining hedgerows with natural or semi-natural habitat pays dividends for increasing biodiversity.33

As a Source and Sink

Hedgerows bring the woodland biome to the farmed landscape and with it, the fruits of the woodland. They are a local, renewable source of firewood, fodder, fruits and vegetables, medicinal plants, and building materials (eg. timber, charcoal, and twine for baskets).34

Hedgerows also act as carbon sinks, more effectively sequestering carbon than the surrounding countryside.35 This happens via litterfall from trees and brush, but also through reduction in erosion on the hillslope scale.36

Soil Improvement

Besides directly building soil through litterfall accumulation, the trees in a hedgerow promote soil health in several other ways:37

Deep nutrient uptake increases the availability of nutrients and minerals.

Decaying root systems aerate and improve physical soil conditions such as bulk density, porosity, and permeability.

Mycorrhizal associations with fungi among some leguminous tree and bush species fix nitrogen.

A cooler and wetter microclimate improves the habitat for soil organisms such as fungi, insects, worms, and microbiota.

An abundance of wildlife directly builds soil through various activities, whether fertilization via droppings, spreading seeds, decomposition, or the disturbance of biomass.

Hedgerow Design

Intercropping

Utilizing hedgerows as intercrops is only recommended in humid tropical or subtropical environments with enough rainfall to forego irrigation.38 They work best in landscapes with soils of moderate pH and in places denuded of trees, with a greater value for tree products. The intercropped hedges must be cut back (to reduce competition for resources) and the green mulch dropped in the alleys between at the time of planting of the crop. Corn is often chosen as the intercrop as it performs better as such than other crops like cassava, soyabean, or groundnuts.

Sun Traps

A style of hedgerow often advocated among permaculturists is the so-called “sun trap” or light funnel. It involves laying a hedge in a horseshoe shape, open towards the equator. It serves to concentrate solar insolation, particularly thermal radiation, so that the interior of the horseshoe is not only protected from prevailing winds but is also warmer by virtue of this reflected energy.3940 This basic formula makes more sense in cooler climates than warmer ones, where high summer temperatures are the limiting factor for photosynthesis. Shelterbelts in these zones could serve an important inverse function as sources of shade at the hottest times of day.

Social Aspects

Hedgerows are seen differently by different people according to their point of view.41 Farmers tend to prefer a more open landscape, which they see as one in which to work and make the land productive, with hedgerows on property boundaries only. Those visiting a landscape with hedgerows (eg. bikers and hikers) prefer vistas of unbroken hedges which provide shade, shelter from the wind, and add natural interest to the scenery. In contrast, those living in a landscape dominated by hedgerows can get the impression of being locked in. Residents generally prefer a middle-of-the-road design philosophy, with some open sightlines to “see outside.”

Creating a Hedgerow

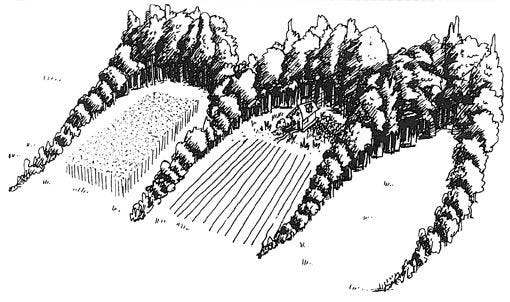

A north-south placement will maximize the solar insolation for crops growing near the hedgerow.42 This effect becomes less important as distance between hedgerows increases. Generally, this effect is small compared to the size of the intervening field, so hedges are best placed where they provide maximum protection from the prevailing winds, both in summer and winter. Placing the hedgerow on-contour allows it to double in an erosional control capacity. Depending on the strength of the prevailing winds, one or two primary rows may be enough. The Canadian Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration recommends up to five rows to protect from north-westerly winds.43

What species to use in a hedge depends on the locality, but also on the intended function of the hedgerow. There is no singular “correct” way to design a hedgerow, though they often involve thorny scrub to aid their function as a fence. Often hedgerow designs follow a national standard, but this is suboptimal for promoting biodiversity.44 Better is to involve as many local species in a hedgerow planting as possible.

The best way to design a hedgerow from an ecological standpoint would be through making connections between previously fragmented patches of habitat, whether that be riparian zones or woodland. In areas with deer or other herbivores that may threaten your crops, a heavily managed, thorny hedgerow bordering the property may be matched with a parallel, less managed and wilder hedgerow to facilitate passage around and past your property, but not through it.

While the trend over the 20th century has been towards the consolidation of larger farms and the removal of hedgerows, this is starting to change as people recognize their ecological benefits. And they are not restricted to rural areas! Those living in suburbs can also benefit from not just the windbreak effects, but also microclimate creation, the establishment of wildlife corridors, habitat for native flora and fauna, water filtration, a ready source of wood and fruits, free biomass for mulching, and much more besides. By expanding current hedgerows and reconnecting the fragmented woodland landscape, locales across the world can enjoy the benefits of “rewilding” in a manner conducive with both human and natural flourishing. ~

Baudry, J., Bunce, R.G.H., & Burel, F. (2000). Hedgerows: An international perspective on their origin, function and management, Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 60, Issue 1, pgs. 7-22. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.2000.0358

Hoskins, W. G. (1955). The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Burel, F., Baudry, J. (1995). Social, aesthetic and ecological aspects of hedgerows in rural landscapes as a framework for greenways, Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 33, Issues 1–3, pgs. 327-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(94)02026-C

Forman, R.T.T., Baudry, J. (1984). Hedgerows and hedgerow networks in landscape ecology. Environmental Management 8, pgs. 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01871575

Böhm, C., Kanzler, M. & Freese, D. (2014). Wind speed reductions as influenced by woody hedgerows grown for biomass in short rotation alley cropping systems in Germany. Agroforest Syst 88, 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-014-9700-y

Burel, F. (1996). Hedgerows and Their Role in Agricultural Landscapes, Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 15:2, pgs. 169-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.1996.10393185

Hedgerows. NERC's Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. (n.d.). Retrieved September 25, 2022, from http://resources.schoolscience.co.uk/ceh/hedges/hedgerows2.html

Lazzaro, L., Otto, S., Zanin, G. (2008). Role of hedgerows in intercepting spray drift: Evaluation and modelling of the effects, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, Volume 123, Issue 4, pgs. 317-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2007.07.009

Burel, F. (1996).

Wild Farm Alliance. "Hedgerows: Living Fences to the Moon and Back." Youtube, 7 Jun. 2022.

Gromke, C., Jamarkattel, N., Ruck, B. (2016). Influence of roadside hedgerows on air quality in urban street canyons, Atmospheric Environment, Volume 139, pgs. 75-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.05.014

Burel, F. (1996).

Baudry, J., et al. (2000).

Oreszczyn, S., Lane, B. (2000). The meaning of the hedgerows in the English landscape: different stakeholder perspectives and the implications for future hedge management. Journal of Environmental Management 60, 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.2000.0365

Lecq, S., Loisel, A., Brischoux, F., Mullin, S.J., Bonnet, X. (2017). Importance of ground refuges for the biodiversity in agricultural hedgerows, Ecological Indicators, Volume 72, Pages 615-626, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.08.032

Burel, F. (1996).

Burel, F., Baudry, J., and Lefeuvre, J. C. (1992). Landscape structure and water fluxes, Landscape Ecology and Agroecosystems, Bunce, R. G. H., Ryszkowski, L., and Paoletti, M. G., Eds., CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 41.

Burel, F. (1996).

Haycock, N. E., Pinay, G., and Walker, C. (1993). Nitrogen retention in river corridors: European perspective, Ambio, 22, 340. https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/6059385

Thomas, Z., Abbott, B.W. (2018). Hedgerows reduce nitrate flux at hillslope and catchment scales via root uptake and secondary effects, Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, Volume 215, pgs. 51-61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2018.07.002

Forman, R.T.T., et al. (1984).

Ibid.

National Biodiversity Data Centre. “Managing Healthy Hedgerows.” Youtube, 2 Dec. 2018.

Hannon, L.E., Sisk, T.D. (2009). Hedgerows in an agri-natural landscape: Potential habitat value for native bees, Biological Conservation, Volume 142, Issue 10, pgs. 2140-2154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.04.014

Pelletier-Guittier, C., Théau, J., Dupras, J. (2020). Use of hedgerows by mammals in an intensive agricultural landscape, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, Volume 302, 107079, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107079

Heath, S.K., Soykan, C.U., Velas, K.L., Kelsey, R., Kross, S.M. (2017). A bustle in the hedgerow: Woody field margins boost on farm avian diversity and abundance in an intensive agricultural landscape, Biological Conservation, Volume 212, Part A, Pages 153-161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.05.031

Burel, F. (1996).

Morandin, L.A., Long, R.F., Kremen, C. (2014). Hedgerows enhance beneficial insects on adjacent tomato fields in an intensive agricultural landscape, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, Volume 189, pgs. 164-170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.03.030

Wehling, S., Diekmann, M. (2009). Hedgerows as an environment for forest plants: a comparative case study of five species. Plant Ecol 204, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-008-9560-5

Hoag, M. (2015). “Designing a Permaculture Hedgerow.” Transformative Adventures.

Burel, F. (1996).

Hinsley, S.A., Bellamy, P.E., (2000). The influence of hedge structure, management and landscape context on the value of hedgerows to birds: A review, Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 60, Issue 1, Pages 33-49, https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.2000.0360

Baudry, J., et al. (2000).

Van Den Berge, S., Vangansbeke, P., Baeten, L. et al. (2021). Soil carbon of hedgerows and ‘ghost’ hedgerows. Agroforest Syst 95, 1087–1103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-021-00634-6

Walter, C., Merot, P., Layer, B. and Dutin, G. (2003). The effect of hedgerows on soil organic carbon storage in hillslopes. Soil Use and Management, 19: 201-207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2003.tb00305.x

Cooper, Leakey, R.R.B., Rao, Reynolds. (2017). Agroforestry and the Mitigation of Land Degradation in the Humid and Sub-Humid Tropics of Africa. Multifunctional Agriculture – Achieving Sustainable Development in Africa. 1 Ed. Chapter 4. Pgs. 23-56. Academic Press, CA. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805356-0.00004-0

Ibid.

Off-Grid with Curtis Stone. “5 Benefits to Using Hedgerows on your Farm.” Youtube, 16 Oct. 2019.

Alladin, E. (2020). “Gardening With Sun Traps and Sun Scoops.” Earth Undaunted.

Burel, F., et al. (1995).

Friday, J., Fownes, J. (2002). Competition for light between hedgerows and maize in an alley cropping system in Hawaii, USA. Agroforestry Systems 55, 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020598110484

Johnston, J. (1997). “Organic Matters: Shelterbelts.” Natural Life Magazine.

Busck A.G. (2003). Hedgerow planting analysed as a social system--interaction between farmers and other actors in Denmark. J Environ Manage. 68(2):161-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-4797(03)00064-1

Images:

"Le bocage du Dorset de l'Ouest" by natamagat is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

"Rabbits in the hedgerows" by Ben Sutherland is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

"File:Windmill Cottage Satellite (hedgerow visible).JPG" by Ggp19 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

"Gunpowder Park hedgerow" by diamond geezer is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“A New Deal shelterbelt survives at a location southwest of Lincoln.” Craig Chandler, Nebraska University Communication